Derek Ross, CLF Executive Director & General Legal Counsel*

UPDATE: Since this article was written, the House of Commons' Standing Committee of Justice and Human Rights reversed the course of government efforts to repeal section 176 of the Criminal Code. The Committee's members voted to retain the provision, with some amendments to "modernize" its language. Bill C-51 will now return to the House of Commons for third reading. Read more here.

The Federal Government is currently cleaning up the Criminal Code, but are they going too far with some of their proposed revisions?

Bill C-51, which received second reading and is currently being studied by committee, purports to repeal a number of provisions that are “obsolete, redundant or that no longer have a place in criminal law.”

A number of these provisions – referred to as “zombie laws” because they’re no longer actively used but technically on the books (they’re alive but not really alive) – certainly belong on the chopping block.

But at least one of these is not like the others.

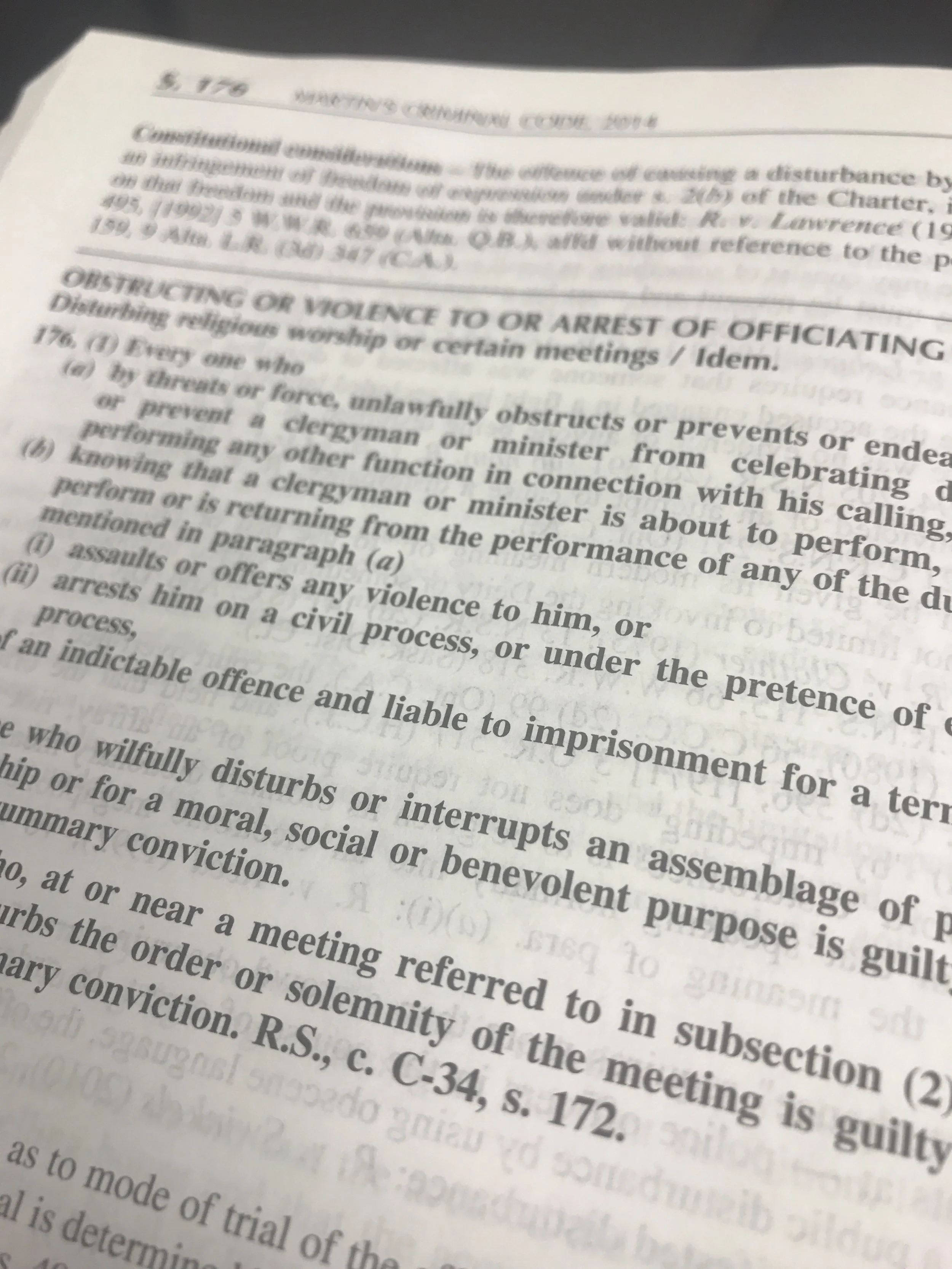

Section 176 prohibits activity that obstructs or interferes with religious officials seeking to perform their religious duties or with “assemblages of persons met for religious worship or for a moral, social or benevolent purpose.” Some of the language of the section may be infrequently used, but what about the validity of its purpose?

In order to qualify as one of the “zombie laws” Bill C-51 targets, section 176 would need to be “unconstitutional”, “outdated”, or “duplicative of more general offences”. It is none of these things, and thus its proposed elimination is puzzling.

Section 176 is not unconstitutional. Canadian courts have consistently applied its provisions and upheld its constitutionality, both for division of powers and Charter purposes.

Nor can section 176 be said to be outdated. It may not be used as frequently as other Criminal Code provisions but it has been repeatedly applied by courts (including the Supreme Court of Canada) and relied upon by police authorities (as recently as June 2017).

Is it duplicative of more general offences? That is the position of the Justice Minister, who has stated that “[m]any criminal offences of general application will continue to be available to address all of the conduct that is prohibited by section 176.” But as explained below, this is far from clear. And even if it were, it does not mean that section 176 is redundant or unnecessary. There may be some overlap between section 176 and other offences, but this is true of many provisions in the Criminal Code. Some frauds are also thefts. Some threats are also assaults. There are many other examples.

This is because Canadian law has long recognized that criminal prohibitions may overlap and cover similar conduct. A person can even be convicted of multiple offences arising from the same matter in various circumstances, including where the different “offences are designed to protect different societal interests.”

Some criminal prohibitions – such as assault – address harms in a broad range of circumstances, but others target specific kinds of harms which can be exacerbated in certain contexts, and therefore serve to protect unique societal interests.

Section 176 is one such example. It serves a distinct, important purpose that no other provision of the Criminal Code serves. As the Supreme Court of Canada held, it protects people who have gathered to pursue socially beneficial activities and “safeguard[s] the rights of groups of people to meet freely and to prevent the breaches of the peace which could result if these types of meetings were disrupted.” It therefore “serves the needs of public morality by precluding conduct potentially injurious to the public interest.” A number of judges have further affirmed that its provisions are necessary for the realization of such fundamental rights as freedom of assembly and freedom of association [see here, and here, and here, for example].

The importance of these rights and freedoms is precisely why a specific Criminal Code provision protecting them – as opposed to a generic provision of more limited application – is necessary. Attacking a religious worship service or peaceful assembly (including an irreligious one) is not just an attack on those directly participating; it is an attack on our Charter freedoms and Canada’s societal commitments as expressed in international human rights law. It is therefore a particularly offensive act and deserving of specific redress in the Criminal Code.

Is Section 176 duplicative?

It has been suggested that most of the activity prohibited by s. 176 is sufficiently covered by either section 175 or section 430 of the Criminal Code.

Section 175 makes it a crime for anyone to “[cause] a disturbance in or near a public place” by “fighting, screaming, shouting, swearing, singing or using insulting or obscene language,” “by impeding or molesting other persons” or by “[loitering] in a public place in any way [that] obstructs persons who are in that place,” amongst other things.

But as the British Columbia Court of Appeal has observed, sections 175 and 176 are “quite different.”

Section 175, for instance, only applies in the context of a “public place.” Section 176 has no such restriction. Further, section 175 only prohibits disturbances that are the result of either violent activity or some sort of verbal disruption such as screaming, shouting, or swearing. Section 176 is not so limited; courts have specifically held that it does not require “shouting or screaming or causing an undue amount of noise”. Rather, under section 176, “it is an offence simply to disturb or interrupt an assemblage of persons met for religious worship, regardless of the motive.”

Indeed, the British Columbia Court of Appeal has highlighted several ways in which ss. 175 and 176 are distinct:

Section 175(1)(a) makes it an offence to cause a disturbance in or near a public place. Section 176 makes it an offence to willfully disturb or interrupt an assemblage of persons met for religious worship, or to willfully do anything that disturbs the order of solemnity of such a meeting. In my view, the sections are quite different. Section 176 specifically targets interference with religious services or worship, but s. 175 deals with a variety of problems.

Section 430

Section 430 also differs from section 176 in several key respects. Section 430 currently prohibits conduct that “willfully … obstructs, interrupts or interferes with the lawful use, enjoyment or operation of property” or “obstructs, interrupts or interferes with any person in the lawful use, enjoyment or operation of property.”

While both sections may prohibit activity or behaviour that interrupts a worship service or assembly at certain places, the former will only offer protection to the extent that a property interest is engaged and violated. So, what of interruptions of meetings, services, or assemblies that do not involve property damage or are not considered to involve an obstruction or interference with the use or enjoyment of property? Gatherings such as outdoor baptism services or other open-air gatherings – which are commonplace in many religious traditions – may not always be protected.

Section 430 is limited to interference with property, not necessarily with people. Conversely, section 176 clearly would apply where an accused deliberately obstructs worshippers on their way to a place of worship. For example, an individual making confrontational remarks to parishioners as they walked into their religious service was found guilty under s. 176. In contrast, s. 430(7) provides a complete defence for anyone “attending at or near” a place for the “purpose only of communicating information.” This has been interpreted broadly to cover any communication that does not “constitute trespass or harassment” or “endanger anyone” or that poses “no potential risk of damage to [property].” This is a much narrower interpretation than the test laid out by the Supreme Court of Canada for s. 176(3).

Perhaps the most significant distinction between s. 430 and s. 176, however, is that they are directed at two different purposes. The former is primarily aimed at upholding property rights, while the latter is directed toward protecting the fundamental freedoms guaranteed by section 2 of the Charter, specifically freedom of assembly, freedom of association, and freedom of religion.

Where Criminal Code provisions serve different purposes, conduct prohibited by one provision may not be considered an offence under another; the requisite conduct, or “actus reus”, for each offence is contextual. As Supreme Court Justice Wilson held, the actus reus of the offence in section 176 is not necessarily the physical act per se but “doing so in a certain context i.e., where it was known that to do so would disturb the solemnity of a religious service.” She further explained that an act which is not otherwise criminal could nevertheless constitute an offence where it results in the disturbance of a religious service:

Just as an act which is guilty in one context may be quite innocent in another, so also an act which is innocent in one context may be guilty in another. To use a simple example, it may be an offence to use foul and abusive language in a courtroom but it may be inoffensive to do the same thing in a noisy tavern or in the privacy of one's own home. While it is, in my view, sound to interpret the Criminal Code in such a way that the appellants' conduct is not characterized as criminal, it is a much more radical step to assert that the Criminal Code could not characterize the appellants' conduct as criminal where the result of such conduct is to disturb the carrying on by their fellow parishioners of their religious services. I would be hesitant, indeed, to accept such a submission.[emphasis added]

The fundamental purpose served by section 176 – ensuring that Canadians can exercise their right to freedom of religion, association, and peaceful assembly without fear or interference – is not specifically fulfilled by any other provision of the Criminal Code. The importance of these freedoms cannot be overstated. They are key human rights guaranteed not only by the Charter but in international human rights law, including treaties Canada has committed to uphold, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. In fact, these international obligations have been interpreted to call for exactly the kind of protection currently provided by section 176.

Section 176 furthers Canada’s international obligations by protecting peaceful assembly and freedom of association

In 2010, the United Nations’ Human Rights Council – of which Canada was a member – issued a resolution affirming the utmost importance of these rights as “essential components of democracy” and “providing individuals with invaluable opportunities.” The UN Human Rights Council called upon all member states, including Canada, to take positive measures to “respect and fully protect the rights of all individuals to assemble peacefully and associate freely” including those espousing minority or dissenting views or beliefs.

In order to ensure the “promotion and protection of the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association in all their manifestations”, the United Nations appointed a Special Rapporteur in 2011. The Special Rapporteur has emphasized that freedom of association and peaceful assembly are “cornerstone in any democracy”, and provide a “valuable indicator of a State’s respect for the enjoyment of many other human rights.” UN Member States – including Canada – therefore have a positive obligation to facilitate these rights, and “such responsibility should always be explicitly stated in domestic legislation.”

Section 176 of the Criminal Code can be seen as an important means of fulfilling this international obligation. As the Special Rapporteur has said:

…States have a positive obligation to actively protect peaceful assemblies. Such obligation includes the protection of participants of peaceful assemblies from individuals or groups of individuals, including agents provocateurs and counter-demonstrators, who aim at disrupting or dispersing such assemblies. […]

The right to freedom of association obliges States to take positive measures to establish and maintain an enabling environment. It is crucial that individuals exercising this right are able to operate freely without fear that they may be subjected to any threats, acts of intimidation or violence… [emphasis added]

Concerns have been raised that repealing section 176 will undermine Canada’s international commitments. Without section 176, private actors could disrupt, interfere with, and obstruct religious services and other gatherings protected by the Charter without legal sanction, unless such conduct fits squarely within narrower provisions of the Criminal Code aimed at different purposes entirely (i.e. upholding property rights).

Protecting minority rights

In a genuinely pluralistic society, citizens must be free to meet, worship, and collectively express themselves without fear of being silenced by reprisal, intimidation, or violence. Canada’s historical reality regarding the oppression of religious and other minority groups – some of which has been effectively prosecuted under section 176 – must not be forgotten.

The provisions now contained in section 176 have a long history – they date back to the British Toleration Act of 1688 which provided freedom of worship for non-conformists, and were expressly incorporated into Canadian law by the Offences Against the Person Act 1861.

This lengthy history does not mean that these provisions are now obsolete or antiquated. To the contrary, concerns about efforts to suppress religious expression and silence minority groups, especially those espousing dissenting views, remain as pressing and relevant today as ever.

The Supreme Court’s recognition that section 176 protects the public interest remains a salient one. The inclusion of section 176 in the Criminal Code demonstrates Canada’s ongoing societal commitment to protect the fundamental freedoms of religious expression and association.

*This article draws from CLF’s brief on Bill C-51 submitted to the Parliamentary Standing Committee of Justice and Human Rights. Special thanks to CLF members Barry Bussey, Kristopher Kinsinger, Philip Milley, Sarah Mix-Ross, Daniel Santoro, and Pastor Joshua Tong for their research assistance, input, and feedback on that Brief.